Tutorial 2: the band structure of bulk silicon (calculated via a supercell)

In this tutorial, we will calculate the KI bandstructure of bulk silicon. The input file used for this calculation can be downloaded here.

Wannierization

While this calculation will bear a lot of similarity to the previous tutorial, there are several differences between performing a Koopmans calculation on a bulk system vs. a molecule. One major difference is that we use Wannier functions as our variational orbitals.

What are Wannier functions?

Most electronic-structure codes try to calculate the Bloch states \(\psi_{n\mathbf{k}}\) of periodic systems (where \(n\) is the band index and \(\mathbf{k}\) the crystal momentum). However, other representations are equally valid. One such representation is the Wannier function (WF) basis. In contrast to the very delocalised Bloch states, WFs are spatially localised and as such represent a very convenient basis to work with. In our case, the fact that they are localised means that they are suitable for use as variational orbitals.

Wannier functions \(w_{n\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r})\) can be written in terms of a transformation of the Bloch states:

where our Wannier functions belong to a particular lattice site \(\mathbf{R}\), \(V\) is the unit cell volume, the integral is over the Brillouin zone (BZ), and \(U^{(\mathbf{k})}_{mn}\) defines a unitary rotation that mixes the Bloch states with crystal momentum \(\mathbf{k}\). Crucially, this matrix \(U^{(\mathbf{k})}_{mn}\) is not uniquely defined — indeed, it represents a freedom of the transformation that we can exploit.

We choose our \(U^{(\mathbf{k})}_{mn}\) that gives rise to WFs that are “maximially localised”. We quantify the spread \(\Omega\) of a WF as

The Wannier functions that minimise this spread are called maximally localised Wannier functions (MLWFs). For more details, see Ref. [20].

How do I calculate Wannier functions?

MLWFs can be calculated with Wannier90, an open-source code that is distributed with Quantum ESPRESSO. Performing a Wannierization with Wannier90 requires a series of calculations to be performed with pw.x, wannier90.x, and pw2wannier90.x. This workflow is automated within koopmans, as we will see in this tutorial.

Note

This tutorial will not discuss in detail how perform a Wannierization with Wannier90. The Wannier90 website contains lots of excellent tutorials.

One important distinction to make for Koopmans calculations — as opposed to many of the Wannier90 tutorials — is that we need to separately Wannierize the occupied and empty manifolds.

Let’s now inspect this tutorial’s input file. At the top you will see that

2 "workflow": {

3 "task": "wannierize",

4 "functional": "ki",

which tells the code to perform a standalone Wannierization calculation. Meanwhile, near the bottom of the file there are some Wannier90-specific parameters provided in the w90 block

38 "w90": {

39 "bands_plot": true,

40 "projections": [[{"fsite": [ 0.25, 0.25, 0.25 ], "ang_mtm": "sp3"}],

41 [{"fsite": [ 0.25, 0.25, 0.25 ], "ang_mtm": "sp3"}]],

42 "dis_froz_max": 10.6,

43 "dis_win_max": 16.9

44 },

The w90 block format is explained more fully here.

We run this calculation as per usual:

koopmans si.json | tee si_wannierize.out

After the usual header, you should see something like the following:

Wannierization

==============

Running wannier/scf... done

Running wannier/nscf... done

Running wannier/block_1/wann_preproc... done

Running wannier/block_1/pw2wan... done

Running wannier/block_1/wann... done

Running wannier/block_2/wann_preproc... done

Running wannier/block_2/pw2wan... done

Running wannier/block_2/wann... done

Running wannier/bands... done

Running pdos/projwfc... done

Workflow complete

These various calculations that are required to obtain the MLWFs of bulk silicon. You can inspect the and various output files will have been generated in a new wannier/ directory.

Click here for detailed descriptions of each calculation

- scf

a

pw.xself-consistent DFT calculation performed with no empty bands. This obtains the ground-state electronic density- nscf

a

pw.xnon-self-consistent DFT calculation that determines the Hamiltonian, now including some empty bands- block_1/wann_preproc

a preprocessing

wannier90.xcalculation that generates some files required bypw2wannier90.x- block_1/pw2wan

a

pw2wannier90.xcalculation that extracts from the earilerpw.xcalculations several key quantities required for generating the Wannier orbitals for the occupied manifold: namely, the overlap matrix of the cell-periodic part of the Block states (this is thewann.mmnfile) and the projection of the Bloch states onto some trial localised orbitals (wann.amn)- block_1/wann

the

wannier90.xcalculation that obtains the MLWFs for the occupied manifold- block_2/…

the analogous calculations as those in

occ/, but for the empty manifold- bands

a

pw.xcalculation that calculates the band structure of silicon explicitly, used for verification of the Wannierization (see the next section)- pdos/projwfc

a

projwfc.xcalculation that calculates the projected density of states, also used for checking the Wannierization

The main output files of interest in wannier/ are files block_1/wann.wout and block_2/wann.wout, which contain the output of wannier90.x for the Wannierization of the occupied and empty manifolds. If you inspect either of these files you will be able to see a lot of starting information, and then under a heading like

*------------------------------- WANNIERISE ---------------------------------*

+--------------------------------------------------------------------+<-- CONV

| Iter Delta Spread RMS Gradient Spread (Ang^2) Time |<-- CONV

+--------------------------------------------------------------------+<-- CONV

you will then see a series of steps where you can see the Wannier functions being optimised and the spread (labelled SPRD) decreasing from one step to the next. Scrolling down further you should see a statement that the Wannierization procedure has converged, alongside with a summary of the final state of the WFs.

How do I know if the Wannier functions I have calculated are “good”?

Performing a Wannierization calculation is not a straightforward procedure, and requires the tweaking of the Wannier90 input parameters in order to obtain a “good” set of Wannier functions.

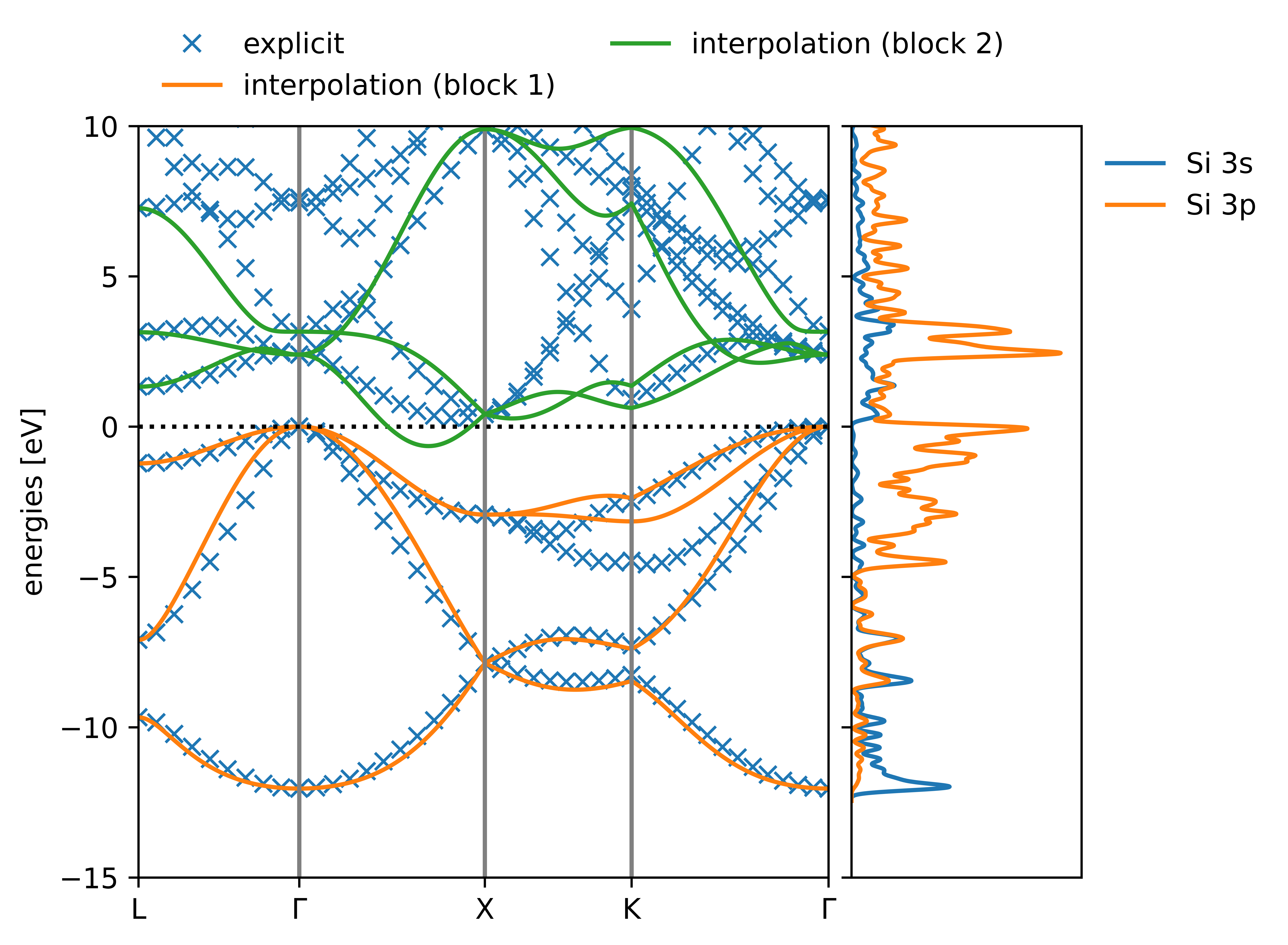

One check is to see if an interpolated bandstructure generated by the MLWFs resembles an explicitly-calculated band structure. (For an explanation of how one can use Wannier functions to interpolate band structures, refer to Ref. [20].) You might have noticed that when we ran koopmans earlier it also generated a file called si_wannierize_bandstructure.png. It should look something like this:

Comparing the interpolated and explicitly-calculated band structures of bulk silicon

Clearly, we can see that the interpolation is no good! (The interpolated band structure ought to lie on top of the explicitly calculated band structure.) The reason for this is that the Brillouin zone is undersampled by our \(2\times2\times2\) \(k\)-point grid. Try increasing the size of the k-point grid and see if the interpolated bandstructure improves.

Tip

Trying different grid sizes can be very easily automated within python. Here is a simple script that will run the Wannierization for three different grid sizes:

from koopmans.io import read

from koopmans.utils import chdir

for grid_size in [2, 4, 8]:

# Read in the input file

wf = read('si.json')

# Modify the kgrid

wf.kpoints.grid = [grid_size, grid_size, grid_size]

# Run the workflow in a subdirectory

with chdir('{0}x{0}x{0}'.format(grid_size)):

wf.run()

Tip

You may also notice a file called si_wannierize_bandstructure.fig.pkl. This is a version of the figure that you can load in python and modify as you see fit. e.g. here is a script that changes the y-axis limits and label:

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

with open('2x2x2/si_wannierize_bandstructure.fig.pkl', 'rb') as fd:

pickle.load(fd)

ax = plt.gca()

ax.set_ylim([-5, 5])

ax.set_ylabel(r'$\omega$ (eV)')

# plt.show() uncomment to view the figure interactively

plt.savefig('2x2x2/si_wannierize_bandstructure_rescaled.png')

The KI calculation

Having obtained a Wannierization of silicon that we are happy with, we can proceed with the KI calculation. In order to do this simply change the task keyword in the input file from wannierize to singlepoint.

Tip

Although we just discovered that a \(2\times2\times2\) \(k\)-point grid was inadequate for producing good Wannier functions, this next calculation is a lot more computationally intensive and will take a long time on most desktop computers. We therefore suggest that for the purposes of this tutorial you switch back to the small \(k\)-point grid. (But for any proper calculations, always use high-quality Wannier functions!)

Initialization

If you run this new input the output will be remarkably similar to that from the previous tutorial, with a couple of exceptions. At the start of the workflow you will see there is a Wannierization procedure, much like we had earlier when we running with the wannierize task:

20 Wannierization

21 ==============

22 Running wannier/scf... done

23 Running wannier/nscf... done

24 Running wannier/block_1/wann_preproc... done

25 Running wannier/block_1/pw2wan... done

26 Running wannier/block_1/wann... done

27 Running wannier/block_2/wann_preproc... done

28 Running wannier/block_2/pw2wan... done

29 Running wannier/block_2/wann... done

which replaces the previous series of semi-local and PZ calculations that we used to initialize the variational orbitals for a molecule.

There is then an new “folding to supercell” subsection:

32 Folding to supercell

33 --------------------

34 Running block_1/w2kcp... done

35 Running block_2/w2kcp... done

In order to understand what these calculations are doing, we must think ahead to the next step in our calculation, where we will calculate the screening parameters using the ΔSCF method. These calculations, where we remove/add an electron from/to the system, require us to work in a supercell. This means that we must transform the \(k\)-dependent primitive cell results from previous calculations into equivalent \(\Gamma\)-only supercell quantities that can be read by kcp. This is precisely what the above wan2odd calculations do.

Calculating the screening parameters

Having transformed into a supercell, the calculation of the screening parameters proceeds as usual. The one difference to tutorial 1 that you might notice at this step is that we are skipping the calculation of screening parameters for some of the orbitals:

42 Calculating screening parameters

43 ================================

44 Running calc_alpha/ki... done

45

46 Orbitals 1-31

47 -------------

48 Skipping; will use the screening parameter of an equivalent orbital

49

50 Orbital 32

51 ----------

The code is doing this because of what we provided for the orbital_groups in the input file:

9 "alpha_guess": 0.077,

10 "orbital_groups": [0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

11 "pseudo_library": "pseudo_dojo_standard",

which tells the code to use the same parameter for orbitals belonging to the same group. In this instance we are calculating a single screening parameter for all four filled orbitals, and a single screening parameter for the empty orbitals.

The final calculation and postprocessing

The final difference for the solids calculation is that there is an additional preprocessing step at the very end:

89 Postprocessing

90 ===============

91

92 Wannierization

93 ==============

94 Running wannier/scf... done

95 Running wannier/nscf... done

96 Running wannier/block_1/wann_preproc... done

97 Running wannier/block_1/pw2wan... done

98 Running wannier/block_1/wann... done

99 Running wannier/block_2/wann_preproc... done

100 Running wannier/block_2/pw2wan... done

101 Running wannier/block_2/wann... done

102 Running wannier/bands... done

103 Running pdos/projwfc... done

104 Running occ/ki... done

105 Running emp/ki... done

106

107 Workflow complete

Here, we transform back our results from the supercell sampled at \(\Gamma\) to the primitive cell with \(k\)-space sampling. This allows us to obtain a bandstructure. The extra Wannierization step that is being performed is to assist the interpolation of the band structure in the primitive cell, and has been performed because in the input file we specified

45 "ui": {

46 "smooth_int_factor": 4

47 }

For more details on the “unfold and interpolate” procedure see here and Ref. [11].

Extracting the KI bandstructure and the bandgap of Si

The bandstructure can be found in postproc/bands_interpolated.dat as a raw data file, but there is a more flexible way for plotting the final bandstructure using the python machinery of koopmans:

from koopmans.io import read

# Load the workflow object

wf = read('si.kwf')

# Access the band structure from the very last calculation

results = wf.calculations[-1].results

bs = results['band structure']

# Print the band strucutre to file

bs.plot(filename='si_bandstructure.png')

# Extract the band gap

n_occ = wf.number_of_electrons() // 2

gap = bs.energies[:, :, n_occ:].min() - bs.energies[:, :, :n_occ].max()

print(f'KI band gap = {gap:.2f} eV')

Running this script will generate a plot of the bandstructure (si_bandstructure.png) as well as printing out the band gap. You should get a result around 1.35 eV. Compare this to the PBE result of 0.68 eV and the experimental value of 1.22 eV. If we were more careful with the Wannier function generation, our result would be even closer (indeed in Ref. [24] the KI band gap was found to be 1.22 eV!)